#3: Up in the Air

“We don’t seem to be getting any higher.”

(Last time, the guys received an unexpected invitation.)

As the dark settled, we drove up the winding road off the state highway to Ralph’s cabin—well, getaway with rustic allusions—in the Adirondacks.

In cargo shorts and a blue-plaid shirt, Ralph waved to us from the front porch. “Welcome! Welcome!” As usual, he was barefoot. He had grown out his hair and cultivated patches of brown stubble on his pale cheeks in some attempt at sleezeball chic.

He gave us a quick tour. The countertops were granite, and the circular stairway climbing up to the loft bedroom was made out of logs with such a thick veneer of stain that they seemed polished. “The real-estate agent called it, ah, carbon neutral,” he boasted when talking about the phalanx of solar panels on the roof. “And you should check out the jacuzzi in the bathroom.”

“Relaxing after a hard day of rhyming?” Pat asked.

“Oh, yes, uh, sure. And look at how big the TV is.”

Ralph had rented this place for the summer. Ralph didn’t like to talk about how much things cost, but Pat once whispered to me that Ralph had a five-figure annual allowance from the estate of his grandmother. On the kitchen table, two bound notebooks were dwarfed by a cluster of beer bottles, a tipped-over bong, and a pile of glossy magazines.

As he opened up a bottle of wine, Ralph said, “You know, it’s good to see you all. It can be a bit, um, remote here.”

“You’ve been here for like two weeks, PL,” Pat said as he dug his cellular phone out of his backpack. “How are you going to stand the whole summer?”

Ralph’s flush was the only answer.

Pat scowled at the small blue brick. “You don’t get much reception out here, do you? I gotta use your regular phone—to check in with Mistah Speakah.”

Ralph’s freezer was full of prepared foods. So we had potstickers and (for Pat, grimace-inducing) edamame. “Tomorrow, after the mountain,” Ralph said, “we’ll have to go to this café nearby. The vegan veal is supposed to be spectacular.”

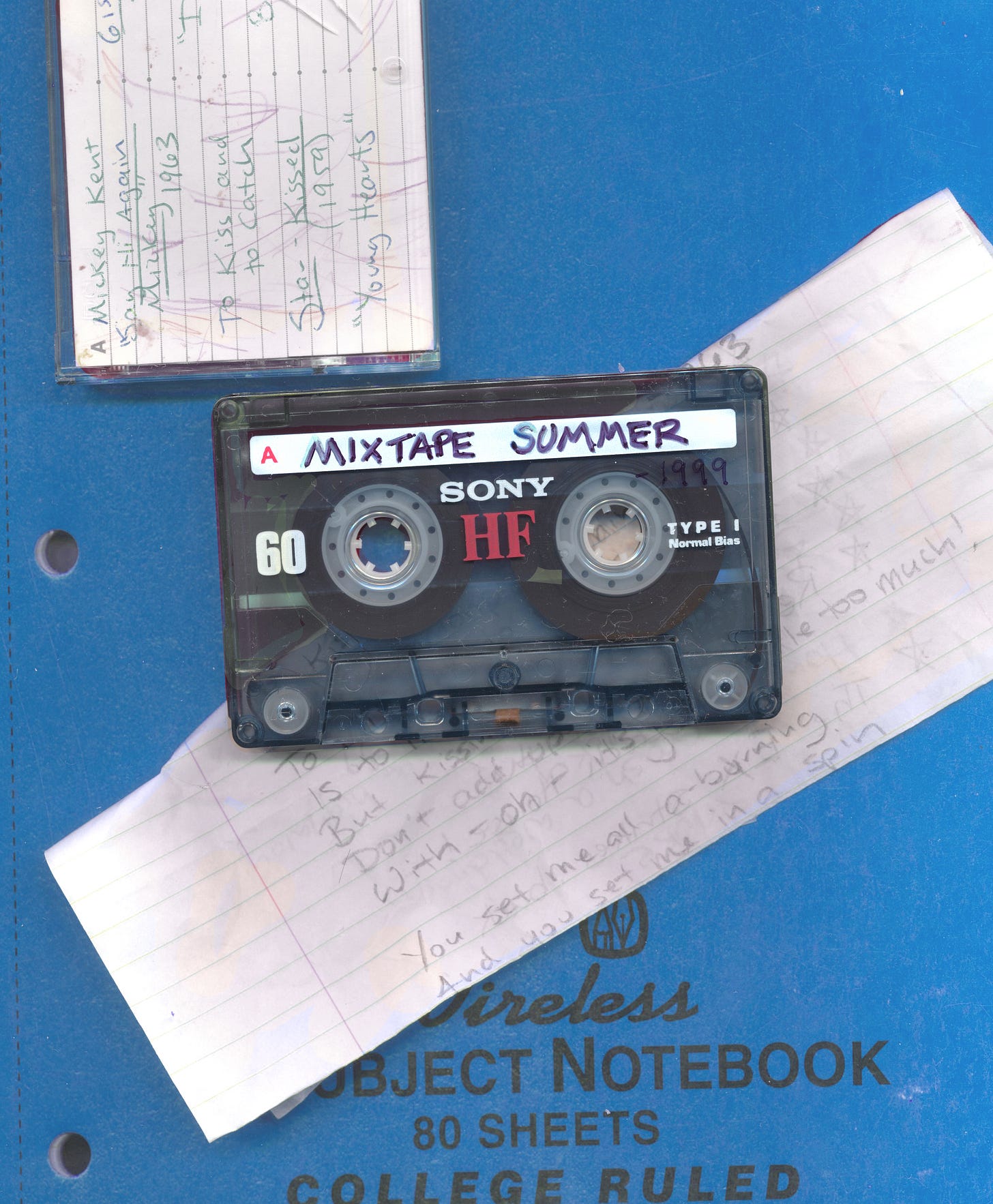

After months, it was strange to see all of us together again. It sometimes felt like memory was what kept us together. Playing poker at Danny’s house. Pat sneaking some cigars from his cousin’s wedding. Throwing up after smoking those cigars. The overnight school trip to Montreal in eighth grade, when our friendship had solidified. Then, college intervened. Then, life. Going on this road trip together was almost a homage to our youth—to what we were then. When Pat listened to Mickey Kent now, how much did he enjoy the music simply because we had listened to it at sixteen? He and Ralph had first started the Mickey Kent thing—as a way of liking something different from grunge and rap and the fading light of rock and roll. At the end of history, a throwback might seem the most promising way forward.

When we talked about going to Kentucky, Ralph slouched forward in his chair—the equivalent of a leap for other people. “A wedding? Well, ah, that could be kind of cool.” Suddenly, his eyes widened. “Oh, Charlie, has Pat told you…”

Pat laughed, even louder than usual, and swung his gaze like a double-barreled shotgun to Ralph. “I already told him, PL, that he’s gotta keep his eyes on the prize this time.”

Ralph’s lips quivered like they were munching on invisible words—and then he turned back to the edamame.

Between Worlds

What is it to share a world with another person? She taught me how to bungee jump and how to make a really good margarita and how to fill a day and a night. We played her favorite board games and spent so many Saturdays at house parties in Cambridge and Sommerville and Allston and Brighton. Gina pulled me from the library with a smirk. “OK, dreamer, time to enter the real world.” Time to enter our world.

When does an embrace become a restraint? Day after day, we built a horizon of habits and associations: what shouldn’t be mentioned, lines in the sand, fallback jokes. Part of sharing that world is holding your tongue. “OK, dreamer…”

Sometimes, I transgressed. I writhed in the harness of habit. “It’s almost like you resent it when I go to the library.”

“Reading books isn’t going to change the world, you know. It’s not living. I just think you should remember that.”

“Not living—what does that even mean? Isn’t that why we’re in college—to read?”

“Or, you know, to start a career.”

Oh, that was it. She was still bitter that I wouldn’t be pushed into one of the tracks—one of the ruts—so appealing to so many around us. “Can’t you at least go to one of the investment-banking recruiting sessions?” she had said.

I didn’t say anything back. I knew when to keep quiet. It was only now, in our own world, that I understood how much self-strangulation was part of a relationship.

Lost in trees and clouds, the mountain peak reached an unfathomable height above us the next morning. It had been a long time since I had tried to climb a mountain. My brother Hank had taken me once, when I had graduated high school. As I struggled on the side of the mountain, mallets pounded on my forehead and played my spine like a xylophone. Yet all that pain washed away in the sudden clarity of the mountaintop. Hank had grinned at me like we were sharing some incredible secret up there, at the doorway of the clouds.

Ours was the only car in the parking lot, and the path up the mountain forked after only a few steps. One way charged up the mountain, cutting through tree and rock with a fierce intensity. The other route slithered alongside a trickling mountain stream and then crawled at a gentle incline upward.

The paths divided us. Ralph and I opted for the steep; Pat and Danny preferred the flat. So Ralph had a proposal: “Why don’t we split up?”

“Well, they both go to the top, right?” Pat said as he considered with crossed arms. “Sure—you’ll take the high road, and we’ll take the low road.”

“You would take the low road,” Ralph said.

The “high road” was a path of rock and leaps, struggles and dirt. Trees lined our way and, though they obscured, they also gave us handholds at a few crucial moments. My hands began to ache from the effort to grip the rock face and pull myself upward. Fire tremored in my biceps.

“Is it supposed to be this hard?” I asked.

“Maybe we should have taken the low road,” Ralph said through a frown.

We didn’t cross paths with anybody. The only other sounds were rippling bird-calls and the rustling of the brush and mountain trees. We had escaped to nature, and the heights rebuked the tentacles of mortal technology. No pavement, no bathrooms, no pay phones—the pinnacle of remoteness.

At a certain threshold, the path became almost pure stone. The dimples of our sneakers dancing across the articulations of rock, Ralph and I teetered from one rocky outcropping to the next. Nothing steady, nothing still. Sometimes, a wild force—rushing frantically forward—was the only hope for balance.

But that very excess of force could also endanger us. Too sudden, too quick, at the wrong instant, and we risked tumbling from the fragmented path.

The continual struggle with steepness eventually wore us down. I tried to dart across a narrow portion of stony path, and I felt like I was slipping a little with each step.

“My muscles feel like putty,” I said to Ralph.

“I feel all stretched out,” he replied, “but I, uh, don’t think my arms are any longer.”

With all our toil, we did seem to be rising. The ground below grew more and more distant. Through the parted fingers of the trees, I couldn’t see the car.

Then we hit a blank wall of rock. It was like a giant hand had taken a trowel and drawn it straight up the mountain. I couldn’t even reach the top of it. The waverings of its face were not deep enough to hold feet or hands.

“It looks like the path is gone or blocked,” I said.

“If there ever was any path,” Ralph said as a little verbal shrug.

I looked around. “What now? Should we jump?”

“I, ah, don’t think we can jump that high.” Ralph shook his head. “I think there’s an easier way.” He turned away from that almost-impossible stone.

“Where are you going?” I followed.

“I saw something back here.”

Beneath a snapped, rotting tree, a path twisted off at an obscure angle. It featured no calamitous caverns or ankle-snapping stretches. After a few steps, it led to soft dirt and clear walking. Perhaps, after all the earlier difficulties, we had now reached the genial reward.

This sort of walk suited Ralph as much as his thrifted t-shirt with the peeling façade of Donald Duck. Ralph pulled his pipe (his preferred method of tobacco delivery) out of his backpack. “You mind if I…”

“Sure.”

With pursed lips, he coaxed a few gray tendrils into a deepening fog. Soon, the thick, jasmine-tinctured plumes of smoke floated around us and blocked out the fainter scents of the forest.

One comfortable step after the other, we no longer seemed to ascend. If anything, the path seemed to dribble downward. “You know, Ralph,” I said, “we don’t seem to be getting any higher.”

Ralph’s faint eyebrows lowered, and he shrugged. “Does it really, uh, matter if we make it to the top of the mountain. We can just let our feet walk wherever. Perspective is all.” His eyes drifted along, maybe perusing some vernal writ. “I sometimes wonder about nature.”

“What?”

“I mean, the poets—the poets of the past were able to look at a tree or a river and just see something mystical and profound in it. They could become transparent eyeballs. Has that ever happened to you—becoming a transparent eyeball?”

I laughed. “I don’t think so.”

“And this whole land used to be nature nature nature. When the first Cudmore came, there was just the barren wilderness here.”

“There was no Cudmore Court?”

Little whinnying chuckles rose from Ralph’s lips. “No, no.” I had known Ralph’s family name before I ever knew him. The Cudmores had settled in our town in the 1600s, and my bus in elementary school had a stop at Cudmore Court. Not that the Cudmores had ever lived there; a real-estate developer in the 1970s had simply labeled the development’s streets with colonial names in order to inflate cookie-cutter suburbia with a sense of history.

“But I look at a tree and find no rapture. I thought maybe that, if I got here, I could,” Ralph continued. He sighed, and the corners of his mouth smoked like an exhaust pipe. “You can’t tell Pat this—he’d never let me forget it—but you and he were right to avoid graduate school. It can be so, ah, stultifying.”

“Danny doesn’t seem to find it that way.”

“Danny’s a man of rationality. But, well, being a poet…We’re all sitting around and scribbling and watching each other. One of my teachers says that there’s poetry all around us. We just need to know how to see it. That’s easy to say.”

He drifted into talking about Mickey Kent. “There’s such a vigor to his voice,” Ralph said. “And his lyrics have such poetry. I think that, if I saw him in person…I don’t know—maybe some of the magic would rub off on me? Is that, ah, silly?”

“No. Not at all.”

“Just a change.” Smoke dribbled from his mouth. “Maybe I should do something really different, like move to Chicago or something. Maybe things are different out west. But that’s what I need: a change.”

I laughed. Maybe it was the smoke, but the air’s flanged molecules caught in my throat. “I understand that.”

A chipmunk darted across the path ahead of us.

“I wonder what that’s thinking right now,” Ralph said. “Of us.”

I shrugged. “Maybe please don’t eat me?”

“Who would eat a chipmunk?”

“A lot of things. Maybe a lot of people.”

“Who’d want to eat chipmunk stew?” he muttered with a sickly frown. He didn’t look like he wanted to ponder an answer to that question. “Haven’t you ever wondered about that—how it must feel to be that chipmunk? Scurrying from tree to tree. I mean, that’s like climbing a skyscraper for us. And they just leap from one tree to the next, careless as can be.”

I thought of the chipmunk’s constant agitation, every moment watching for the predatory hawk or coyote. Always twitching nose and quivering body, the frantic burst from one spot to the next. The chipmunk raced because it knew that every day its life could end in a predator’s jaws—a final splat of blood and pain.

“Isn’t it nice to just think of nature?” Ralph said as he swung his arms wide. “There’s such a, such a pristine peace to it.”

I smiled.

He looked around. “It’s gone now. But that’s life—always flowing. You rake the leaves in the yard, and you’ve got a whole new yard. Jump in the ocean, and it’s not the same anymore. Everything’s always next.”

One moment dangled on the next. Ralph marched along with a happy, spondaic gait. Through the pipe-cleaner horizon of pine needles and spindly trunks, we got a hint of the sky. The path continued to wind; we blew along the circuits of the wind.

The serpentine bars of trees broke at a sudden vantage point, as we walked into a clearing. A haze like wax paper slid across the green-capped peaks of the Adirondacks.

“What a vision!” Ralph called. A few dying gray coils drifted from the embers of his pipe.

Maybe because of the length of our wandering or the elevation of those hills or the demands of the view, we sank down on two level stones to have lunch. The lukewarm water was cool to my throat, and the peanut-butter sandwich mushed easily in my mouth.

Hefting his water bottle and sandwich, Ralph declared, “I feel like a shepherd here—in Arcadia! Just look at these clouds, Charlie. Look…look at the sky!” The swollen, fanciful puffs drifted in an ocean of air.

I stretched out on the stone. It had drunk of the sun’s light, and its warmth bled into my palms. Pulling a flannel shirt from my backpack, I stuffed it under my neck.

Ralph and I gazed at the azured vault above and the lazy train of clouds dragged along by the summer breeze. “That cloud looks almost like a horse,” I said.

Ralph offered a slight hum in appraisal as he looked past the book resting on his chest. “Indeed. It does look like a horse, even rearing up a little.”

“Or sorta like a pig.”

“It’s got a snout like a pig.”

“Or even like a lobster.”

“Very much like a lobster.” Ralph yawned. “You know, it could be almost anything you want. A walrus, a rhinoceros, a giraffe.”

“You think it looks like a giraffe?” I asked.

Ralph hesitated for a moment. “It’s possible.”

I shrugged and closed my eyes. I let the contention pass from me. “I guess,” I murmured in the white darkness.

I sighed and then drank deep of the mountain air. Ralph’s tobacco had receded to only a shadow of a scent. My arms felt heavy. Like the clouds, my thoughts drifted.

The sun warmed my face. My cheek tingled at the bright strokes. My joints released—the gentle stretching of a bow, the loosening of muscle. Two great billows, my lungs kneaded the emptiness and air—faint, fading streams through my lips and nostrils. Slowing. Slowing.

I felt the snare-drum of my pulse at my neck—slow, slow, slow. My fingers uncurled as my palms turned upward to weigh the sky. The emptiness—the vacuum’s vast encumbrance—stretched my hand flat. The miles of air fell over my body. Each heft of my chest a struggle with emptiness—the crushing fathoms against the boney fingers arched over my lungs.

Beep beep beep beep the timer on my digital watch rang out. Groggily, I pressed one of the buttons on the side of the watch. We had said we would turn back after two and a half hours.

“Ralph,” I said, “time to go.”

“Oh, there will be time,” Ralph said, rubbing his face. He tossed aside the book that he had been using as an eyeshade.

“What is it?”

“Petrarch. Some of his writings…letters.”

I picked up the slim volume and read from a random page. I thought in silence of the lack of good counsel in us mortals, who neglect what is noblest in ourselves, scatter our energies in all directions, and waste ourselves in vain show, because we look about us for what is to be found only within. I wondered at the natural nobility of our soul, save when it debases itself of its own free will, and deserts its original estate…

“See? Isn’t that tiring?” Ralph had relit his pipe, and nimbus-trails of smoke rose from the bowl.

“I wouldn’t say that.” Petrarch conjured some vague echo of yearning. But—but—ah, but Ralph’s pipe smoked beside me like a beacon of fog. And the gray mist ebbed and flowed and coagulated into little clouds, which curled and rewove and faded as they drifted on the flat canvas above.

While we took the same path to the base, the ground felt strange and soft to my tired feet. Even the surest step had a moment of trembling, as though I walked upon drops of water.

Danny and Pat hadn’t made it to the top of the mountain, either. “We walked and walked and walked,” Pat explained. “I think we were rising for a while, but we must have missed a turn or something, and then somehow we ended up in this forest.”

Danny added. “I took some pictures of some very fine examples of metamorphic rocks.”

“But no summit,” I sighed. I looked up and couldn’t even tell anymore at which peak we had been aiming.

“Maybe there is no path to the peak,” Pat added.

“There must be,” I replied. “There has to be.” The existence of that path suddenly seemed very important to me. “Maybe it’s just hidden or something. Maybe we’re starting from the wrong place.”

For dinner that day, we ate at the Electric Café, which was, Ralph averred, the place to be in the summer’s poetic scene: “Everyone goes there—Marc Trully, Greve Sanchez, Sandraa Fox-Woole—everybody just sitting there swapping stanzas.” But, though her picture was on the wall, Sandraa Fox-Woole was not there; neither were Marc or Greve. We were the only patrons, and the vegan veal’s tofu almost expurgated Ralph at the first taste, but he valiantly ate on. Ralph did buy a bright red t-shirt with the motto “Verse for Wear” sketched out in white lettering, so at least he got a trophy from his visit.

As we walked back to the car across the empty parking lot, Ralph’s shoulders drooped as though they were made of running ink. “It could have been so much different,” he exclaimed.

“Yes,” Danny said, “but it wasn’t.”

Mello Schemes

The smoke swirled like tentacles out of Pat’s mouth. “You weren’t kidding—or exaggerating—PL. This is the good stuff.”

“And it’s so mellow. It’s like…it’s like floating on a cloud. Mello Mello—that’s what they call it.”

“Poetic.”

“So, Pat, about the letter—”

“Dude, you almost blew that one, like you always do when you’re high or drunk…”

“No way—”

“Way. Like my ‘surprise party’ in college.”

“Yeah…” And Ralph’s voice dissolved in a fizz of chuckles.

“Man, heh heh, man you gotta trust me on this. If we talk about that letter, you know and I know—we all know—that he’s gonna build a maze for himself. He’s like the master of mindgames. Like grandmaster. Grand. Master. And he plays them against himself.”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“We need to keep our plans fluid. We’ll talk about Seattle later. Let’s just play it cool. Like the Mello Mello. The wedding—that’s the thing.” He smiled. “And just for the record—I’m not inhaling….”

The giggles rose in clouds.