(Last time, Charlie and friends set off across the country. Glimpsing a face on the highway, Charlie now sees her again playing at a county fair.)

The bandana stretched across her forehead as her neck bent over the violin. The other three members of the quartet stood on stage with her. Her eyes were closed, like she was listening to the heartbeat of the violin. Her hand jumped up and down, like she was weaving some melody in the air—no, like the melody had filled her body and it was craving for release—no, like she had become the melody. Her loose green dress swayed. I had never before seen how music was not confined to the hands or the lips or the throat or the intermediary instrument. Instead, it transformed you from toes to hairtips. Like a lightbulb’s filament, her slender frame bore the fantastic weight of so much light.

How were people munching on tempura and cotton candy and lukewarm hotdogs? Why wasn’t there a crowd pressing the stage? How could people do any more than watch and listen to this?

I stepped closer to the stage, and, with a musical flourish, the song ended.

The scattered few dozen people in picnic tables applauded. Some of them, anyway. The four girls bowed. As she smiled and bowed, her eyes must have glanced at me. Suddenly, she stopped and bent forward, examining me like I was some mystery who had bizarrely stumbled into her life.

The claws of the tired speaker system scratched the air. “Let’s hear it for the Bridgetune Quartet.”

I clapped again.

“That’s her, isn’t it?” Pat said from behind me as the quartet walked off the stage.

“Yes. Yes, I think so.”

A skinny guy with a green mohawk—a holdout from the 1980s—struggled onto the stage carrying an amp. He must have been the next act.

“So what’s next?” Pat asked. I could hear the smile in his voice.

“What’s next? I mean, they’re gone.”

“Like you should let that—” Pat began before halting. “And are they even gone?”

I followed the direction of his waving hand, and then my throat tightened. She was approaching. At her side was a girl whose hair was pulled up in a messy bun, dark tendrils in her face like a dragon’s spines. Above green eyes, her purple-painted eyelids were set like a predator’s.

“So this is the fan club,” the other girl said.

“Lana,” she said. Then she looked at me and—smiled. Her teeth caught the sunshine. “Hey, this is gonna sound kinda weird—”

“You’d be surprised,” I somehow stumble-said.

“What are you doing here?”

What was I doing here? I wasn’t sure. I had leaped from one moment to the next and was somehow standing on this weathered grass.

She smiled again and maybe realized how that question had sounded. “It’s just funny because I think I’ve seen you before. Your car has all the bumper stickers, right?”

Oh, the bumper stickers. They formed an ever-growing collage of Pat’s impulses since he was seventeen: a baseball glove, a snowboarding brand, a Dazed and Confused quotation, advertisements for every Democratic presidential nominee since 1980, and (something he had picked up from a talk-radio host) a blue rectangle with the slogan, Eliminate the EPA…it’s them or us.

“That’s us.” Then, my thoughts caught up with my words—she had noticed us. She had noticed me. “And I’ve seen you, too, I think.”

“Isn’t that funny?” she said and laughed.

I laughed, too, and suddenly all the awkwardness evaporated. “I’m Charlie, by the way.”

“Bonnie,” she said. “Nice to meet you. And this is Lana.”

Right after I introduced Pat and Danny, Lana pounced. “So you guys like the musical sideshow circuit?”

“Lana—”

“Bonnie, you and I both know that this is not how they marketed to us. And we’re not even getting paid.”

“Lana.”

“I’m just saying, we’re not.” Her eyes swung back at us. “So?”

“We’re going on a trip,” I said.

Bonnie smiled again. “So weird—so are we. We’re on, like, a mini-tour on our way to a wedding.”

“In Kentucky,” Lana added. “It’s going to be a real hoedown. Also for free.”

“Lana, you can’t charge your cousin.”

“And so what are you guys going to see on your trip?” Lana asked.

“Mickey Kent,” Pat said with a flourish of his hand.

Lana squinted. “Who?”

“You’ve gotta be kidding me. You. Have. Got. To be kidding me.” Pat dropped his jaw like he was struggling with the open air. “You can honestly tell me you’ve never heard of Mickey Kent?”

“He’s a singer from the sixties,” Danny explained.

Pat winced at that blasphemy. “He’s a singer from the present. He’s still around, Danny-boy, and the classics never die.”

As Pat readied his five-minute stump speech on the value of Mickey Kent, Bonnie turned to me and said, “Hey, I’m kinda thirsty. Want to get a soda or something?”

Even just a few steps away from the others, the air seemed to open up around us. “It is weird,” I said, “to see each other like this. But not creepy-weird, right?”

Bonnie laughed. “I don’t think so. You don’t drive around every day looking for a body you can throw in the trunk of your car, do you?”

“Not every day, no. Today just might be a special day.”

It had been a long time since I had talked to a girl this way. Since Gina and I had broken up, I had gone on a few dates, but there had always been something awkward about them. I usually felt like I was playing a part (a living, breathing human being), like a painted mask of a rigid smile was on my face. Now, though, I felt nimble and free.

Everything about Bonnie was so fluid—her arms swung wide and her dress swirled around her bouncing knees. Maybe playing the violin had helped cultivate some wondrous responsiveness in her body. “I always liked fairs. They’re like a vacation from the world.”

“Kind of like road trips,” I said. Or at least we hope they can be.

“Sure.” She grinned.

At some booth sponsored by the Lions, we got two cans of soda (oh, only five dollars for both of them). The old man in the mesh baseball cap put them on the counter, and she grabbed them both and gave one to me. The tips of our fingers brushed each other. The soda’s fizz danced in the back of my throat.

“Your friend Pat has a lot to say.”

I smiled. “He’s in politics, so he believes that the whole world is just waiting for his opinion on everything. And I say that from long experience.”

“So you go way back?”

“He’s probably my oldest friend—like first grade.”

“Wow,” she said. “That’s a long time.”

I shrugged. “It’s a lot of firsts—first grade, first girlfriends, first jobs, first cars. I was even his first campaign manager.”

“For what?”

“Senior class president. I don’t know why I agreed. Who can manage a Category-Five hurricane? I couldn’t.”

“Did he end up winning?”

“Pat usually wins.”

She tilted her head. “So you must have done a pretty good job, then.”

“So what brought you to the violin?” I asked.

“I think it’s more that music brought the violin to me. As a little kid, I always loved singing and everything. My mom said that more music came from me than from all my brothers and my sister combined. My dad’s a big jazz fan, but, once in a while, he’d play classical—like Mozart or Beethoven. I loved the strings. Of course, I didn’t call them the strings. I called them the fairy part. In elementary school, the music teacher had this video where you could see someone playing each instrument. And the clip of the guy playing the violin featured Beethoven, from one of his concertos. Since that was a song I knew, and it was the fairy part, the violin was the instrument for me. It was one of those moments when you just know.”

“Yes,” I murmured.

“It was difficult to learn how to play at first. But being hard was part of it. I’d get frustrated, but I’d never want to give up. Even tuning the violin was fun. I’d twist those little pegs until I got it just right. Playing music’s really about listening, you know—that’s what it really is.”

“I could tell that,” I said, “when you were playing earlier today.”

“You could?”

“Yes. I could.”

“Well, talk about listening—I’ve been blabbing on and on about music...”

“I love to hear about you and music.”

Every detail about her life seemed like the shore of a magical new ocean. She grew up west of Boston, and was now just about to start at the conservatory in the city. She and Lana had been friends from college, and they had met the other two members of the quartet at a summer workshop last year. They had played some gigs over the past year, and had a few more lined up that summer.

“So you’re going to see Mickey Kent, huh?” she asked.

“You know him?”

“My dad is like a—like a mega-fan. I mean, he’s still got a lot of the old records he bought when he was listening to this stuff as a kid.”

“Really?”

She almost blushed. It was very cute. “Totally. You know that there’s a fan club for him?”

“Yeah, yeah. Pat and Ralph—he’s another friend—are both members.”

“Platinum preferred?”

I laughed. “Platinum preferred. That’s crazy. Well, they’ve always wanted to see that music festival he runs out in Montana.”

“Kentstock? You’re going to Kentstock? My dad has always wanted to go.”

“He should come along,” I said with a grin.

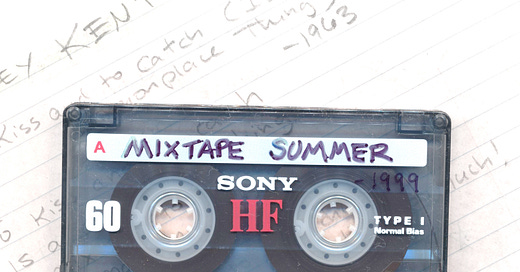

“I’m sure he’d love to. He goes to Kentstock East almost every year.” The same weekend as Kentstock, “Kentstock East” happened in a small theater in the Boston suburbs near our town. Mickey Kent fans from the Boston area would descend upon the town to trade memorabilia, listen to cover bands, catch up with other Micksters.

“Oh, wow. Pat’s gone there a few times.”

“And what about you?”

“Me?” I said with a laugh. “No, I’ve never gone.”

“And now you’re making the long journey out west to the original.”

“That’s Pat—that’s not me. He wants to see the real thing and check out the Micky Kent museum and everything else.”

“So why are you going?”

“I wanted to do something different—get out of my usual rut.”

Just then, Lana was there. “Hey, Bonnie, we have to get going if we’re going to make it to Kim’s house for dinner.”

“Oh, yeah,” Bonnie said—an infinitesimal deflation of two syllables.

Lana reached her arm around Bonnie and started to pull her away. Their heads were together. Then, Bonnie was shaking her head. And laughing.

Lana turned around. “Actually, Charlie, you know what would make that wedding even more fun?”

“What?”

“If you and your boys showed up. Even Pete can come.”

“It’s Pat.”

Lana ignored Pat’s correction. “That is, if you’re up to it. The First Baptist Church in Vauville, Kentucky. Saturday. At two o’clock. See you there—or maybe not.” Then they ran giggling away.

“Can you believe this?” I asked my friends.

“That Lana,” Pat said, “thinks she is so clever. Pete. Really.” Rarely had I heard such breathless praise from him.

Danny furrowed his brow. “Do they even have the ability to invite us to the wedding?”

“We were invited to crash it,” Pat replied. He grinned. “And obviously, we have to go.”

“But we’re supposed to be doing the Appalachian Trail on Saturday,” Danny rejoined. “That’s what we put on the schedule.”

“Oh no!” Pat stretched out his hands like a high-school Hamlet. “Spend two days walking the Appalachian Trail or crash a wedding in Kentucky! That’s an impossible choice—how could we ever decide what to do? I mean, Charlie, is there even a choice to be made there?”

“This is getting ridiculous, Pat,” I said and started walking toward the car. But I also couldn’t keep the feeling of a smile from the buds of my cheeks.

“Of course it’s not ridiculous. I mean, you can, despite yourself, be charming, Charlie. That was some serious game there.”

“Oh, yeah, totally. Totally. First of all, we have no idea if she’s even remotely interested in me. She could even have a boyfriend—she probably does!”

“But I think the thing worth asking,” Pat said with the confidence of someone who believed he was winning an argument, “is whether you are even remotely interested in her?”

“I’ve only just met her. I don’t even know her.”

Pat replied, “Like that matters? Sometimes, Charlie, it seems as though you don’t believe in fairytales at all.”

“That’s one of the problems of growing up. Look, yes, she’s nice. And yes, it would be fun, maybe, to do something totally random like go to this wedding in Kentucky.” And yes, a thrill like a mermaid’s tail whirled through my stomach at the idea of making that journey. “But what would it even be for?”

“Does it have to be for anything?” Pat asked. “Can’t it just be anything?”

“But what would it be?” One more exercise in folly and disappointment?

I started the engine, and a Mickey Kent song swung out of the speakers. The toots of horns punctuated the sliding whines of trombones. His voice reeled through.

What a gas, what a joke, What a gas, what a joke, Like something woke, like it could last, Like when I saw you I saw something, Like something was some beginning, Like it wasn’t only dreaming With you. And yet I hear the laughter— Is that all I was after? Just a little bit of laughter? And the laughter’s broke—could it be? Well, if it’s all a joke, Well, then the joke’s on me.